Beyond the Plate

March 6, 2023

From biochemistry and nutrition to history and anthropology, UNT food scholars are carving out new paths of discovery.

TEXT: HEATHER NOEL

PHOTOGRAPHY: AHNA HUBNIK

As an expert in plant biochemistry, UNT professor Ana Paula Alonso knows a lot about plant behavior, but she’s learned throughout her career to expect the unexpected.

“Plants don’t stop to amaze me,” Alonso says.“They are these little chemical factories that produce our food, produce our oxygen — they do so much for us that we don’t even know.”

In the UNT BioDiscovery Institute’s Environmental Science Greenhouse, Alonso’s team of researchers spend hours each week documenting a collection of novel soybeans as part of a project that could one day prove soybeans as a viable protein alternative. In UNT dining halls, chefs and administrative staff are designing menus and operations to be more environmentally sustainable and opening their spaces for research about food literacy and choice. And across academic disciplines at UNT — the only comprehensive Tier One research university serving the North Texas region — research is developing food as a lens to be more inclusive in public planning and access, better understand human behavior and build deeper perspectives of culture, collective identity and history.

The plants UNT biochemists are examining aren’t typical soybeans found in the top-producing fields of the U.S. upper Midwest or Central-South region of Brazil. From seed to maturity, they are monitoring soybean plants that have been modified in a United Soybean Board-funded research project focused on increasing the seed’s oil content and nutritional value.

Soybeans may not be a common vegetable consumed directly on American dinner plates, but they play an important role in the U.S. food supply as a primary component of poultry and livestock feed. And in the future, soybeans could be more regularly consumed by humans as a healthful protein alternative based on the research underway at UNT and other institutes around the country.

“Our team wants to improve the oil content without affecting the yield for farmers and protein because soybeans contain all the essential proteinogenic amino acids that are indispensable for health,” says Alonso,who is associate director of UNT’s BioDiscovery Institute.

Alonso is co-principal investigator on the project, and along with former UNT research scientist Cintia Arias and research assistant Duyen Pham, they are part of the nationwide team of interdisciplinary researchers studying soybeans. Alonso’s lab is one of the few in the world that uses metabolic flux analysis, which is a way to quantitatively examine the processes cells undergo to sustain life, to study the biochemical composition of plants, a leading reason Arias chose to work at UNT following her doctoral studies in Argentina and Austria.

“Transgenic plants — those whose DNA have been genetically modified — take a really long time to grow and to analyze,” Alonso says. “We want to learn from the process along the way.”

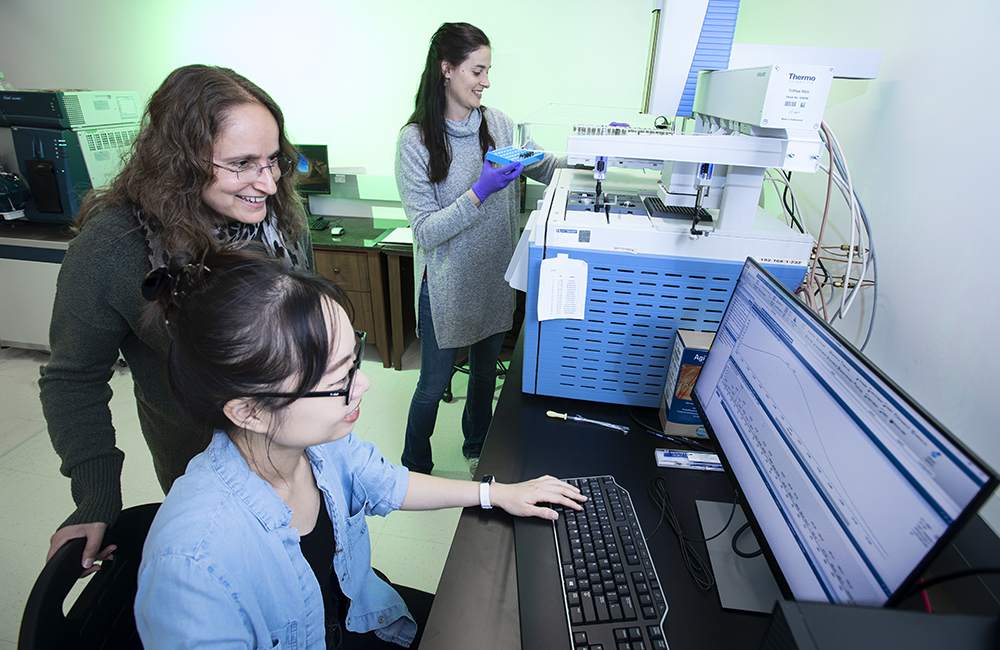

UNT professor Ana Paula Alonso (top left) along with former UNT research scientist

Cintia Arias (top right) and research assistant Duyen Pham (bottom right), are part

of the nationwide team of interdisciplinary researchers studying soybeans.

UNT biochemists are following the flow of carbon in each plant. Their results can help inform soybean breeders on how to further tweak their plant cultivars to reach the goal of improved oil content and nutritional value. Long-term applications of their research could introduce a soybean fortified with the same Omega-3 fatty acids found in fish.

Alonso’s colleagues in the BioDiscovery Institute also are making new discoveries in plant science that will lead to future breakthroughs in more sustainable crops such as wheat, corn and coffee to meet the market needs.

For instance, Kent Chapman, Regents Professor of biological sciences and director of the BioDiscovery Institute, and Ashley Cannon, a former UNT postdoctoral scholar and research molecular biologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, are illuminating how heterotrimeric G-Proteins are involved in N-Acylethanolamine (NAE) signaling in plants — findings that could ultimately be key in understanding how plants could thrive even in their earliest stages under stressful conditions.

Richard Dixon, Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of biochemistry and molecular biology, and his team have furthered the understanding of engineering plant molecules called tannins. Their results could be used to not only make food more nutritious for animals, but potentially improve food supply and limit global warming.

“The world’s population is projected to reach nearly 10 billion by 2050 and global climate change is expected to reduce agricultural productivity,” Alonso says.“These factors will only increase global issues related to food security, making research solutions vital for our future.”

Living Laboratories

Food is more than sustenance. UNT Dining Services, the largest self-supported food service department in North Texas, is dedicated to making food as fresh, local, delicious and healthy as possible — without compromising its environmentally sustainable practices. That commitment takes continuous innovation such as opening the nation’s first all-vegan collegiate dining hall and first collegiate dining hall in Texas to be free of the “Big 8” food allergens — as well as staying up-to-date on the latest best practices in the industry like it has done with the hydroponic garden, Mean Green Acres, that reduces the university’s carbon footprint. UNT is helping set industry standards and collect insight to inform changes as a member of the groundbreaking Menus of Change University Research Collaborative.

Launched in 2012, UNT was one of the early members of its research collaborative in 2014, which is co-led by The Culinary Institute of America and Stanford University. Menus of Change is working to realize a long- term, practical vision integrating optimal nutrition and public health, environmental stewardship and restoration, and social responsibility concerns within the food service industry and the culinary profession.

This past October, UNT hosted the annual meeting of the research collaborative, which includes a membership of 69 college and university food service and academic programs across the nation.

“We are cultivating the long-term well- being of people and the planet one student and one meal at a time,” says Peter Ballabuch, executive director of UNT Dining Services.

Additionally, the collaborative is studying food choice and behaviors right on campus. Priscilla Connors, registered dietitian and an associate professor in the College of Merchandising, Hospitality and Tourism, leads Menus of Change-tied campus studies.

“Menus of Change has opened up our dining halls as these living laboratories to collect data in real time,” says Connors, whose other research includes a USDA- funded study on food choice and waste in school cafeterias and upcoming studies on consumer literacy of food labels.

Past research includes how food label language impacts food choice and student understanding of unhealthy versus healthful fats in foods. An upcoming project will focus on students’ knowledge of caffeine content in commonly consumed drinks. Dining Services has hired hospitality management student Nancy Hinojosa to serve as an undergraduate research fellow helping manage future Menus of Change studies at UNT.

Lessons of the Past

Other scholars are taking lessons of the past to help inform the years to come.

“Food history is really at the core of food studies research at UNT,” says history professor Michael Wise, an environmental historian of food and agriculture in modern North America with the forthcoming book Native Foods: Agriculture, Indigeneity, and Settler Colonialism in American History. “Much of the research is looking at the past as a sort of reservoir of alternative models and solutions to current problems.”

Food is a building block to all human behavior.

Wise and history professor Jennifer Jensen Wallach, a historian of African American food, identity construction and race- making, are leading efforts to grow UNT’s food studies program, which offers an interdisciplinary food studies certificate for undergraduates as well as a $5,000 graduate-level food history fellowship funded by The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.

“Food is a building block to all human behavior,” says Wallach, who has been both author or editor for a number of books that use food to talk about broader cultural, economic, racial and social issues. She’s currently studying food and disabilities, especially for people with autism.

Other UNT history professors are studying food, from Rachel Moran's research on the history of nutrition and federal policies that she shares in Governing Bodies: American Politics and the Shaping of the Modern Physique to Sandra Mendiola Garcia's research on food and labor outlined in Street Democracy: Vendors, Violence, and Public Space in Late Twentieth-Century Mexico. Nancy Stockdale is editing a book about the foodways of the Middle East. Wallach has written three books focused on food history, including Getting What We Need Ourselves: How Food Has Shaped African American Life.

Cultivation of food studies at UNT goes back nearly a decade when Wise and Wallach first started assembling faculty beyond history that were interested in this area of study such as professor David Kaplan, who specializes in the philosophical investigation of food, and professor Lisa Henry, a medical anthropologist studying food insecurity. Informal gatherings and university-sponsored events such as the 2015 conference, “Moral Cultures of Food: Past and Present,” and a 2021 visit from James Beard Award-winning Chef Bryant Terry, which was part of the UNT President’s Lecture Series, helped to further collaborations and raise awareness of food studies at UNT.

The fruits of engaging a multidisciplinary focus on food research at UNT is evident in a project Wise is working on with his history colleague Sandra Mendiola Garcia and faculty members Nathan Hutson and Laura Keyes in public administration. They are planning to turn underutilized green spaces on campus into micro gardens growing historically relevant food crops to the North Texas area following the ancient Mesoamerican concept called milpa.

“From ancient history through the present, there have been many alternative forms of agriculture that communities have used that don’t require mono-cropping of a cleared field,” Wise says. “Using the milpa system on campus will serve as a bedrock for understanding different ways of seeing our landscape as well as fuel inquiry about the intersection of food, identity, community and environment.”

Read more about student food scholars at UNT.